Flatland climbers

In the 1970s, a group of mountaineers started despising the myth of a hard and pure climber.

by Susanna Marchini

In 1970, Bob Dylan published his eleventh studio album New Morning among student protests and cultural changes. Four years later, Gian Piero Motti, an excellent alpinist and author for Rivista della montagna magazine, was inspired by this album and used the Italian translation of it — il Nuovo Mattino — to name the youth movement he led that would forever change alpinism and climbing in Italy. Enrico Camanni is an alpinist and journalist who participated in this movement and embraced this philosophy. “There was a big misunderstanding among old-school alpinists, about who was better and who did more difficult things.” says Camanni: “The real point was destroying the idea of military heroism behind mountain expeditions and transforming climbing into a game.”

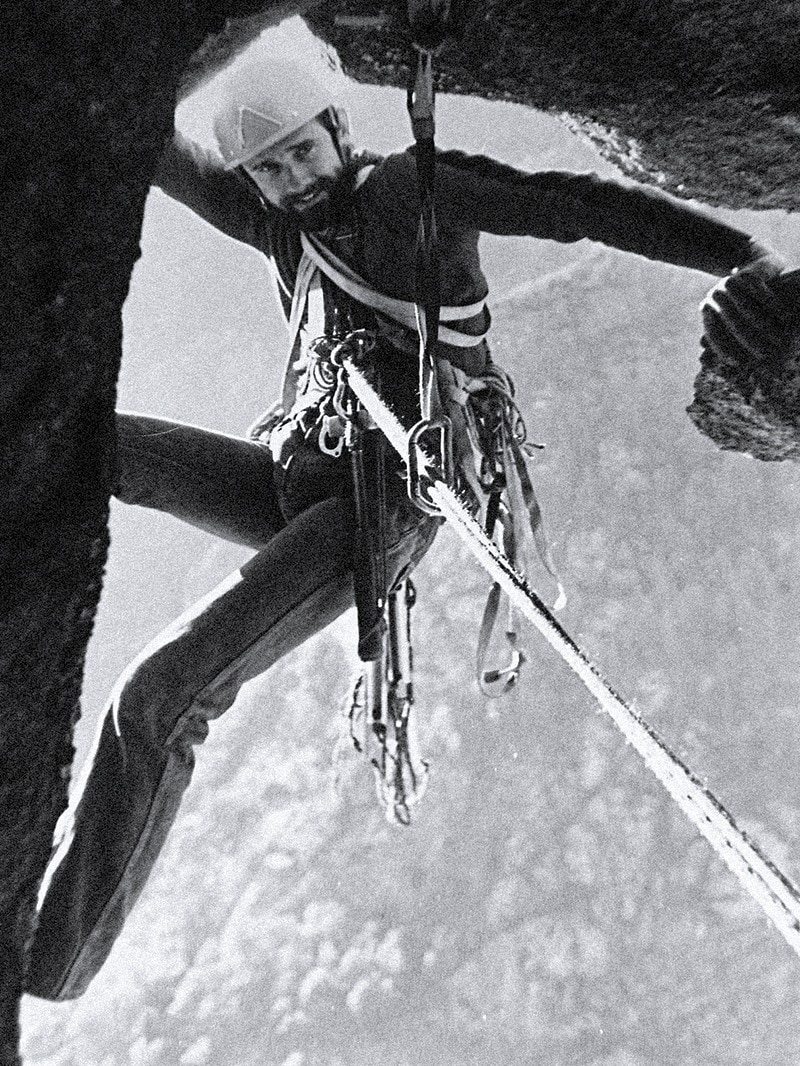

Until that turning point, alpinism had been synonymous with enormous effort and highly uncomfortable outfits. “Going to the mountains felt like an obligation,” says Camanni. “You had to reach the top or else your climb was worthless, you had to follow certain strict and old directives, it was more like an army activity: you wake up early, you leave early, you always carry a heavy backpack.” Il Nuovo Mattino despised the figure of the hard and pure alpinist, the rite of the summit at all costs, the struggle of the Alps. They rejected classic garments and replaced them with jeans, T-shirts, and lighter rubber shoes.

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes,” said Camanni, quoting Marcel Proust to explain how the aim of the group was to move the attention from the peak of the mountain to easier walls, to transform climbing into a fun and creative activity rather than a duty. “If you climb in the valley at 5,000 feets above the sea level, you have less stress, there are no glaciers, there is more sun; it is a whole different thing than what you could do on the top of a mountain. Also, the complexity of the peaks made it an elitist activity, so Nuovo Mattino unhinge the cliché; they open up climbing to everyone, transforming it into a democratic sport. When you start to take away the taboo of the summit, the taboo of the cold weather, the taboo of the heavy backpack, in the end, you make climbing free.”

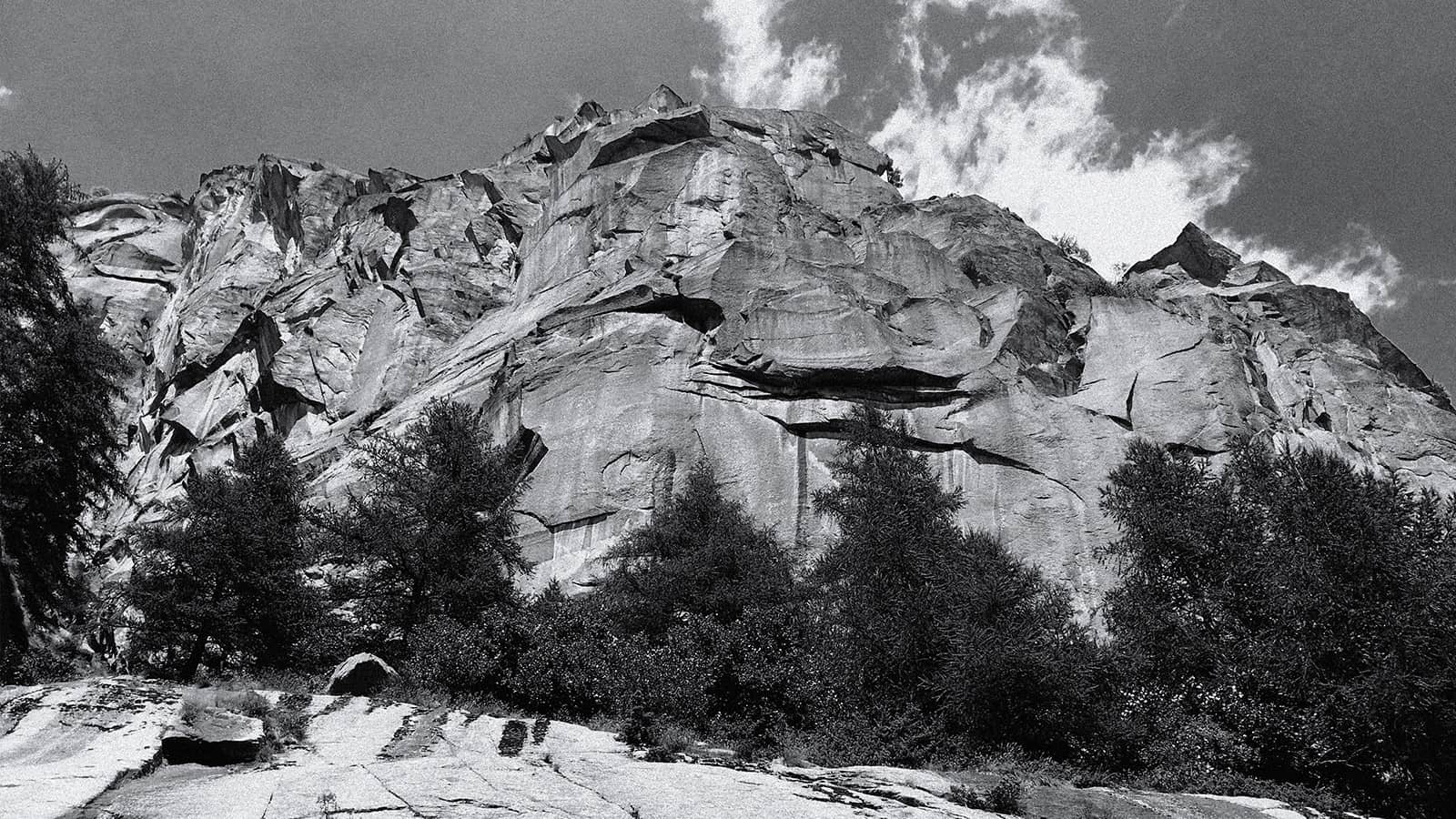

The real innovation was to focus on something that had always been there and tackle the challenge in a new way. Inspired by the myth of Californian climbing, Il Nuovo Mattino found new walls and called them Caporal and Sergeant, in response to the legendary El Captain of the Yosemite Valley. Says Camanni: “For three years we imitated those long-haired people that lived in tents for months at the base of the walls, climbing when they wanted to, sunbathing when they didn’t. In California, cliffs have always had different features: there are no hostile climatic conditions, so for them, it was normal to climb those kinds of walls.”

What made the Italian movement different from the American one, was an intellectual push which derived from 1968 cultural references. It’s no coincidence that the movement grew in the urban areas of the most industrial cities of Italy. Il Nuovo Mattino included people from all backgrounds and social classes, but this equal democracy was reached thanks to the personality of Gian Piero Motti and other young cultured men who looked for a complimentary but not conflicting truth with the urban experience and industrial society.

Camanni says, “I think our story was exceptional from a literary point of view. Gian Piero Motti and Andrea Gobetti were the ones sharing their experiences, their thoughts, their adventures with a completely different style and when I started reading this new language, all the rest seemed old.”

Although Il Nuovo Mattino was influential for a young generation of climbers, it didn’t last long; with the mountain approach becoming less elitist, that act of transgression became a commercial affair in less than 10 years. The rebellion was incorporated into the system to generate profits, whoever believed in the dream of living the mountain experience forever, became exasperated: they knew that, sooner or later, it was time to come back to reality.

Adventure has been extensively abused by commercials and social networks, and even the desire to escape daily routine is exploited. “What’s the point today of talking about adventure with internet, smartphones, helicopters?” Camanni asks. “Now, if we don’t know everything about an itinerary we don’t even leave because we have doubts. If alpinism and climbing hadn’t had that component of adventure, I think I would have done something else. We always have to find unknown areas in our lives today, everything is too planned out. It makes me laugh when travel agencies promote their offers as a guaranteed adventure, this is absolute nonsense. I love the fact that more and more people are passionate about the alpine environment, but without desire and with too many indications, it’s not interesting anymore.”

At the same time, there are always more and more people that find their happiness outside urban areas with the same desire of changing the current equilibrium. “Now, everyone makes his or her own life trying to live for the best, sometimes in an ethical and balanced way. When we were young, we wanted to change the world in a more decisive way. Probably we didn’t change anything, still, our short revolution was meaningful.” This story must be a nudge for the population that is now struggling with a more and more anti-human society; as Enrico says, “don’t take for granted the freedom and wellbeing that you inherit from the previous generation, nothing lasts unchanged forever, even a small transgressive act can be useful for a better future.”