Chronemics and cultures

We plan for the future through calendars and diaries. But not every culture looks at time in this western way.

by Lynn Cole

Time, as we know it in Western culture, is linear and sequential. It moves by seconds, minutes, days, weeks, months, and years. Once time has passed, it’s done. We plan for the future through calendars and diaries. But not every culture looks at time in this Western way. There are variations on this theme, which have been explored through history, anthropology, psychology, and physics — a whole other wormhole to get sucked into. But time as a form of cross-cultural communication is becoming more important in our ever-shrinking world. Hence, many organizations are looking at time perception through the lens of Chronemics to analyze cultures and how they relate to time.

Edward T. Hall, an anthropologist and cross-cultural scholar, analyzes the give-and-take of human relationships with time in his book The Silent Language. He concludes that there are two main viewpoints: The first are “polychronic” cultures that can attend to multiple events at the same time. They value relationships and traditions and are focused more on the overall outcome of an event than on punctuality. The second are “monochronic” cultures. These cultures view time as tangible, as a commodity whereby “time is money,” taking care of one event at a time.

Dr. Thomas J. Bruneau, a non-verbal communication expert, takes Hall’s theory a step further. He coined the term Chronemics as “the study of human tempo as it relates to human communication.” This includes observations and theories about our use of time, how time is perceived, valued, and structured, in the context of communication within cultural systems. Chronemics has become an umbrella term for communication and cultural analysis. The question is, are these factors too simplistic for global cultural analysis?

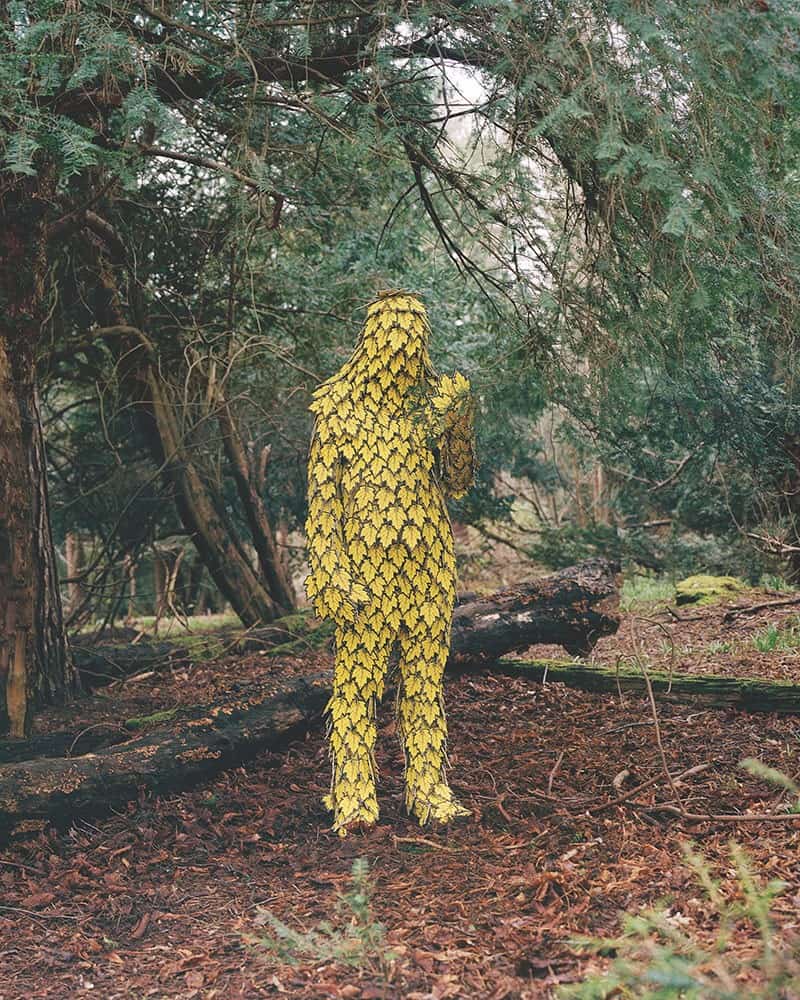

In her cross-cultural communications research, Dr. Sana Reynolds emphasizes a third way that different groups perceive time – according to the natural world. This cyclical time perception is different than polychronic-monochronic time cultures where people control their time.

“What caught my attention was that I kept bumping into multiple proverbs that told me that people were not in control,” says Reynolds. “It was striking how much emphasis was placed on the role of nature and that human beings were just another manifestation of life within the scope of this force and therefore had to live in accordance with nature.”

Reynolds explains how this cyclical time manifests across the world, in what she calls a three-part view of time. Strict time is followed in the United States, Germany, and Switzerland, and beyond punctuality, it means people are focused on time in general. Flex time is attributed to more Southern European countries like Spain, France, and Italy, which are more easygoing about time focusing more on relationships than punctuality. Then there is cyclical time, where nature dominates how people tell time. She says that it’s even possible to see different time perceptions across the same country using Switzerland as an example. “In Zurich, it’s the clock that reigns supreme and therefore the culture is strict or monochronic. Then you have another area in the country known as Romandie which is French-influenced and there you have polychronic or flex time. Finally, there is the Landquart region where Johanna Spyri wrote, Heidi, and there, agrarian or cyclical time perception is part of the culture.”

Cyclical time is not clock-bound and is attributed to more traditional societies. Raymond Cohen, Professor of International Studies at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in his book, Negotiating Across Cultures, says: “The arbitrary divisions of the clock face have little saliency in cultures grounded in the cycle of the seasons, the invariant pattern of rural life, community life, and the calendar of religious festivities.”

Western society’s globalization and cultural narratives rely on strict time constructs to control the populace on a wide scale. In North American culture, time is money, time marches on, and time is spent. Life is scheduled right down to what people do on their time off. How people and cultures are valued is entwined in this measure. Groups and individuals who don’t fall in line with these constructs may be marginalized.

Reynolds posits that when it comes to how western culture thinks about human communication there is the accusation of a lack of respect for the way in which other cultures operate due to time perception. This is changing. Scholars are becoming very aware of this bias and are saying that greater attention needs to be paid to this paradigm.

Edward Said, a professor at Columbia University, explored this idea in Orientalism, explaining how the West’s representations of “The East”— the societies and peoples who inhabit the places of Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East — may create a communications bias. This brings up questions of cultural relativity and linguistic relativity, which try to give each culture its due, but in practice, may alienate ‘exotic’ cultures.

Deep in Brazil’s Amazonian rainforests, there is a group where time does not exist as it does for us. The Amondawa tribe, rather than tracking their lives in years, changes their names according to different stages of life and clan-affiliation. Yet, they speak Portuguese in order to trade and can count and discuss time in a polychronic way as is found throughout the rest of the country.

Chris Sinha, a professor at Hunan University who studied the Amondawa, says understanding how different cultures perceive time, can help us understand what it means to be human. He writes, in When time is not space The social and linguistic construction of time intervals and temporal event relations in an Amazonian culture: “We can’t and shouldn’t try to stop change, but we should help empower people like the Amondawa to determine their own future and keep their language and traditions alive.”

Cultures who do not follow the polychronic-monochronic view of time should not be expected to change how they perceive time. But with the introduction of modernity which includes health care, communication devices, and electricity also might come — as in the Amondawa example — a need to communicate outside of their norms, for survival.

Differences in time perception affect the way people behave and how we live and work together as humans. As individuals, we may time-warp through polychronic, monochronic, and cyclical times, but cultures do not, which can cause diverse views of time across the same country. For now, businesses, academia, and international organizations are turning to Chronemics to help them understand and communicate across cultures. Who knows what the future holds as cultural groups become more connected, but in the meantime, time marches on.