Brave new work

Aaron Dignan helps companies navigate the unchartered territory of the workplace of the future, advocating for open information.

by Francesco Salonia

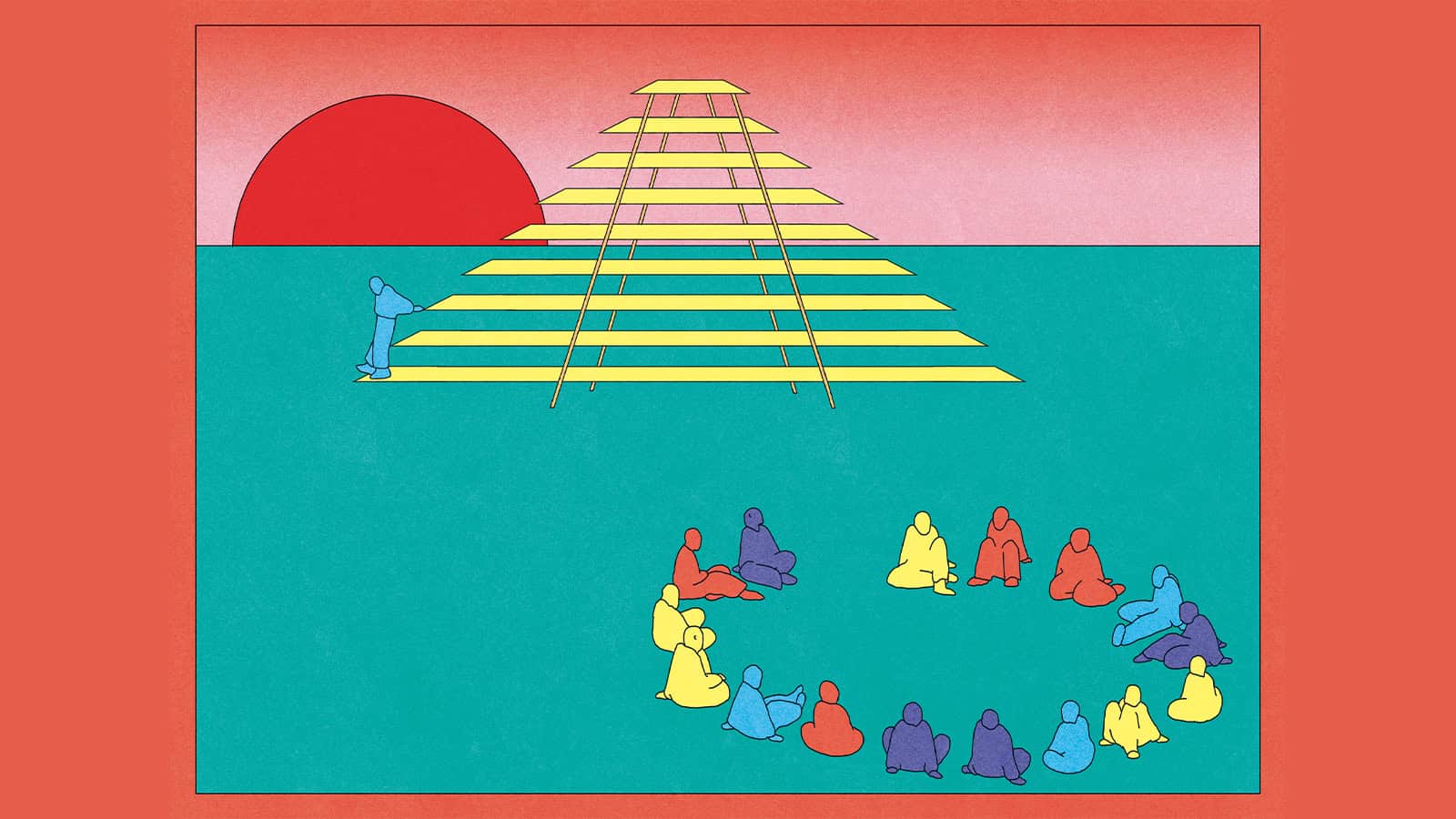

As the forces of globalization, technological innovation, and digital business models continue to shape our economies in unexpected ways and multiply the degrees of complexity in which companies operate, the century-old model of centralized, top-down management is crumbling. Still, the illusion of command and control provided by traditional power systems, and defining the shape of this “new way” to begin with, is hard to drop.

Aaron Dignan, founder of New York-based organizational design agency The Ready and author of Brave New Work, has made a name for himself by helping companies navigate this uncharted territory. To him, the power equation seems easy enough to decipher and yet, is beautifully complex to explore in the depth of its organizational, and human, implications. Dignan says: “The thing about power is that it really connects to your ability to make decisions. And decisions are what fundamentally shape and drive the firm. If you think about the distribution of power, it’s really the distribution of efficiency. With all the dynamics, all the change, all the competitors and the situations happening that we need to be adaptive to, the risk is greater when you have a single decision-maker (or a small number of them) that might not see the full picture.”

Distributed authority, in other words, translates to a finer level of sensemaking that allows us to be smarter on the market. Furthermore, power-sharing means companies can make decisions faster — if we wait for information to travel up and down the organizational ladder, we are likely to miss a great deal of chances to do something right, at the optimum moment.

But make no mistake: one could hardly argue that just by sharing power, organizations magically turn into better, smarter places. The flip side of authority distribution, in fact, is information transparency. Dignan continues: “How are people going to make good decisions if they don’t have all the information? And one of the features that’s interesting about a complex, dynamic environment is that it’s not always clear who needs to know what, or what matters. The right information that might lead to a breakthrough could be hiding in some document, it could be hidden in a long Slack chat, or could even be buried in someone’s head.” We are looking at a 180-degree shift from the old model, in which we could afford strict, slow information flows simply because things didn’t change fast enough. Writes Dignan: “Information was power, and hoarding information was an advantage both individually and organizationally. But today, the real advantage is your ability to process information — how fast can you make sense of it? It’s less about the recipe for Coke, and more about Amazon and Google’s lightning-fast data processing.”

The solution? Defaulting to a place of open information across an organization, and making exceptions only if there’s a good reason. The benefits of such an approach far outweigh the downsides — in terms of people’s accountability, participation, strategic alignment, and continuous improvement.

But where do you draw the line? Dignan makes the point that even highly secretive processes, like compensation and performance management, ought to be open. “Why can’t we hear the conversation about our own performance if we’re going to have that? What is the thing that’s being said that we can’t hear? It feels very paternalistic and secretive. And then, if you want to get radical — why do we even have promotions, raises, and all of that stuff anyway? In a real talent marketplace, like the one in which The Ready operates, people set the rate at whatever they want it to be. And if it’s too high, people won’t work with them. All the situations we are afraid of happening, if we open up information or evidence that the system is not correct — there is either bias in terms of unfairness, or people who are paid fairly are not perceiving the fairness because they don’t understand the broader context of information: their performance, their value, what the firm cares about, and so on.” In both cases, we have a problem.

The concept of achieving control through transparency and power distribution might seem paradoxical, but for companies that have undertaken this course, the business case seems pretty solid, as Dignan explains in his book. In the process, the old rulebook must be scrapped almost entirely, leaving the organization in a sort of ruleless horror vacuum in which people begin to exercise their autonomy and develop ownership. But how do you know how much rule is enough rule, and how much is too much? Dignan explains: “There are fundamentally two kinds of systems in terms of authority — the system where you can’t do anything until you get permission, and the one where you can do anything until we tell you that you can’t. If you’re granting permission, then you’re in a wild goose chase against complexity because you have to map every scenario. A lot of people will sit on their hands because they’re waiting for permission to do whatever their heart already thinks they should do. In the other scenario, you basically build the rule when you need it. Who should decide what, for right now? Everybody. Anybody. Whenever. But as soon as we see there’s confusion, there’s frustration, there’s tension, there’s a mistake that we made four times in a row … Now, the principle is not enough. Now we need a mechanism.”

Of course, distributing power doesn’t mean eliminating it — that is impossible. Dignan says: “There is always power in the system — it’s just in different forms and amounts. There’s formal power, and then there’s informal power — in the form of relationships, reputation, persuasion. You can’t get rid of that, but you can be aware of the way power manifests itself in the organization and try to reduce it when you feel it is causing problems. For example, I think reputational power is fine for the most part. It’s earned power that is always being adjusted. And if someone’s exercising it, they’re using something they earned and have to maintain. I just think it’s really healthy to constantly have discussions about this — at this moment, in this decision, what kinds of power are coming into play? Are we doing this because we think it makes sense, or just because Phil is a really good presenter, or because he runs the budget? Let’s constantly check in with that and make sure that we are OK with the kind of power that is being exercised in any decision.” Awareness of, and participation in power can, in fact, regulate it so that it doesn’t turn into coercion and violence — which not only makes for short-sighted decisions in a high-complexity environment, but certainly contributes to people’s detachment and an entropic loss of trust in the system.

A clear, eudemonic purpose; a basic set of principles and mechanisms that employees can truly consent to, and decide to join (or not join); full transparency of information and freedom to act. It is unfortunate that this ethical, non-coercive form of self-determination can really only happen within the closed walls of a few enlightened organizations — at least for now. Dignan says: “I think when we lose ethics, it’s usually when people feel like they’re removed from decision making. There’s distance. There are people we can point to that are not ‘us’ — ‘they are making me do this’, or ‘it’s not my company’. But when you have more participation and more perspective, when you’re taking in more sense, when you have noble purposes that are pursued with participation, I think you get ethics as a result.”

Could this kind of environment really be everyone’s cup of tea? Are there “evolutionary traits” that individuals must display to fit into this new vision? Dignan challenges the premises of this question. “The reality is that we’re not fixed and the system will inform greatly how we show up, what we’re capable of and what we expect of each other — that is, if the system is robust enough, embedded enough, clear enough.” Having said that, there are traits that predict an individual’s success in a high-transparency, high-participation organization. “It’s about learning agility at the end of the day. It’s whether or not people fundamentally believe they are in control of their lives and they can inform and shape what happens to them. Because the only way to navigate this environment and make it better for yourself is to take action — if you don’t like something, you have to engage with it. You don’t have a lot of caretakers in a system like this, at least not formally. You don’t have managers or HR people or others looking out for you, checking in with you, stroking you. You have to figure out what makes you happy, and go pursue it on your own.”

And it’s also about a healthy relationship with our egos. “There’s a difference between living from ego and self-confidence. In one of our recent Brave New Work podcasts, co-host Rodney Evans said, ‘The ego is like the bouncer outside the nightclub of your identity — it’s trying to keep out certain things and let in other things.’ I think we need people who are aware of their ego and who can check in with it from time to time and be like, ‘let that in.’ People who are committed not to being right, but to being open, curious, and learning — open to the generosity of spirit that comes with this approach.”