Sonic identity

In a world where sight no longer conditions our perception of reality, how can we communicate and create relationships through sound?

by Riccardo Trabattoni

The sonic turn

For centuries our society has relied almost exclusively on the sense of sight to spread a culture’s ideas and values. And since culture is a dynamic system, following the evolution of the elements that define it, the aesthetic and stylistic principles of visual communication have also changed.

Let’s take as an example art nouveau born between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as opposed to nineteenth-century stylistic paradigms and the imposition of an industrial aesthetic, with its linearism, sinuosity and the representation of naturalistic motifs. Futurism, the avant-garde movement of the early 1900s, influenced by wars, social and political transformation, which through its artistic movements expresses a new beauty: speed, dynamism. The rise of war propaganda and art deco, and, fast forward to recent history, pop art, hyperrealism, post-media visual arts. Brands and marketing have made these visual assets one of the most valuable resources for communicating with the public.

In the last decade, however, a new socio-cultural awareness has developed which is decisive for the enhancement of the world of sound: sight no longer totally dominates our perception or understanding of reality. In the artistic field we talk about sonic turn, but many now refer to audio renaissance.

Close a gap

The rise of digitalization, the evolution of our auditory and marketing culture has certainly influenced our way of living, perceiving, and creating sound. However, sonic branding is nothing new, it has a deep history and has made its way from ancient times to today thanks to a natural process in our brains, which associates sounds with reactions and emotions—we never stop hearing, even while we sleep we are able to perceive vital information from specific and distinguishable sounds.

But how did we come to associate sounds with brands and how is this scenario evolving?

If we wanted to really dig deep into the history of auditory branding, we would probably have to go back to 400 AD when the Roman bishop Paulinus of Nola introduced the use of bells in Christian churches to call the faithful to prayer—an excellent sound-Christianity association. But without going over millennia of history in detail, we can highlight some moments that have defined sonic identities as we know them today.

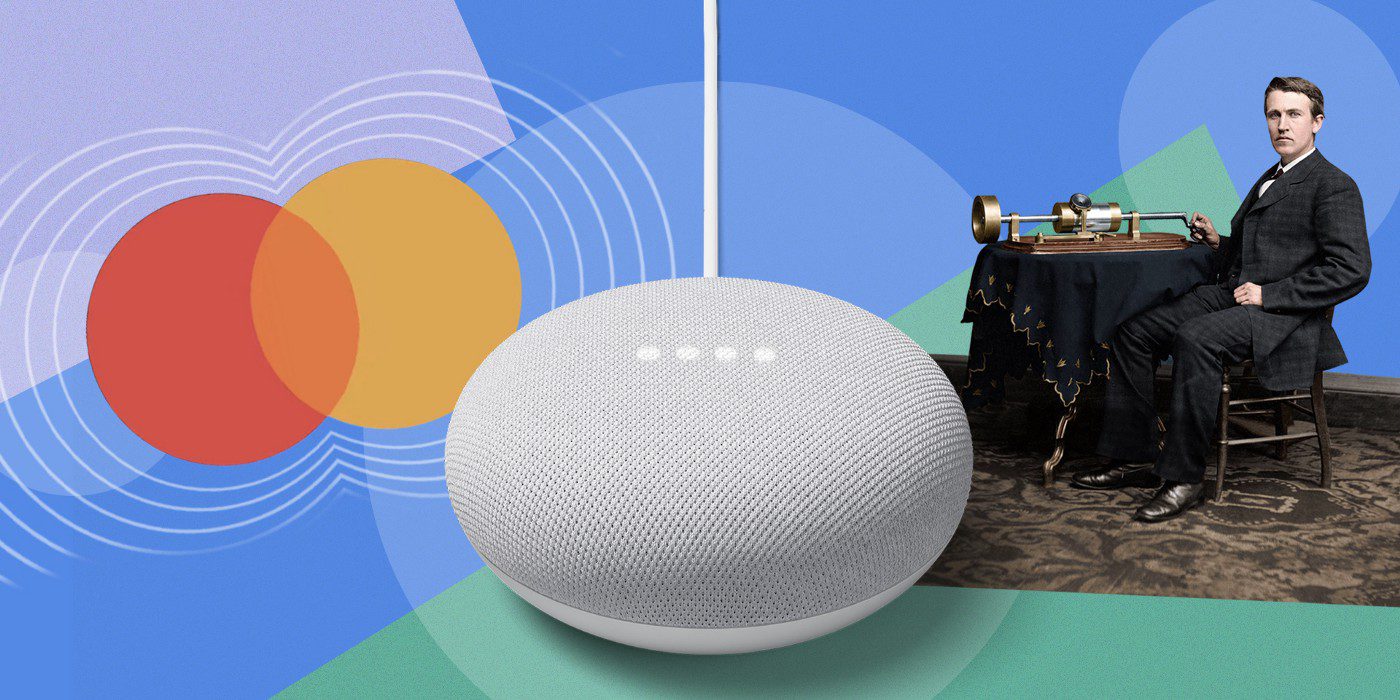

1877 – Thomas Edison invents the phonograph, the first device for mechanical recording and sound reproduction. Before that, all human musical knowledge had been passed down orally.

1890–1930 – Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, developed the concept of conditioned reflex. To sum up: a stimulus can cause a certain involuntary reaction in animals and humans. At the center of Pavlov’s experiment were the unconditional reflexes of his dogs, specifically salivation, at mealtimes. Pavlov demonstrated that by associating the dog’s meals with the sound of a bell several times, he could cause them to salivate. Salivation was therefore induced in dogs by an artificially induced conditioned reflex.

1920 – The idea of spreading sound content to the masses begins to materialize. It is the first radical innovation in mass communications after the invention of printing. Two years later, the BBC, one of the oldest radio stations in the world, was founded. It fulfilled the need for a new language to interact with consumers. The rhythmic and memorable rhymes of the then jingles become the preferred marketing strategy for brands that want to attract listeners’ attention.

1950 – Thanks to technological innovations in the field of sound, soundtracks are now an integral part of every film and film composers explore sound and music as conveyors and activators of emotions, laying the foundations for modern sound identities.

1980 – French radio guru Jean Pierre Baçelon coined the term ‘la marque sonique’ after archiving, analyzing, and categorizing several radio commercials and concluding that ads with sound branding elements gained greater recognition, success and sales.

1994–95 – The years that marked history. Intel debuted its famous sonic logo, the bong sound, which is now estimated to be played every five seconds around the world. Nokia launches the iconic monophonic 3310 ringtone, and the following year, Brian Eno composes—ironically on a Mac—the Windows 95 startup melody.

2003 – Justin Timberlake sings I’m lovin it which after six months at the top of the Billboard chart appears in a McDonald’s ad becoming the soundtrack for the brand’s first global campaign—even today the dynamics behind the writing of the song, which eventually became a symbol of the McDonald’s brand, are not entirely clear.

From the mid-2000s onwards, digitization accelerated the impact of innovation in the media sector: we experienced the boom of smartphones, the birth of social networks, the first voice assistants and the introduction of music streaming platforms into the lives of millions of people. Thus in the last decade a gap has arisen between the content provided by the world of advertising and the actual involvement that the public has with brands when it comes to products, services, and experiences. Today, sonic branding seeks to bridge this gap, not limiting itself to providing just a catchy jingle, but rather offering a strong emotional charge to consumers and creating a coherent experience throughout a brand’s customer experience.

Towards a new aural dimension

As we have seen, especially in the last 10 years, the changes that have taken place have significantly influenced the evolution of sound identities and their exploitation by brands, which have understood that sound plays a vital role in the ubiquity of digital media. Furthermore, today sound is increasingly integrated into everyday products—from household appliances, to cars, to jewelry—and the market for voice-activated products is constantly expanding. This brings us to our evidence: if we have always been used to interacting with objects through sight (eyes), and touch (fingers), in the future we will also use hearing (ears), and our voices. Visual images and symbols, which were previously vehicles of important messages, are slowly giving way to a new aural dimension of information and interactions, pushing brands to be more and more audible as well as visible.

The challenge, therefore, will be to know how to combine these two worlds and be able to produce sound outputs that are as pleasant as they are functional—sounds that won’t pollute an already chaotic environment that is overloaded with stimuli.

Sound identities and where to apply them

At this point a legitimate question comes up: what is a sonic identity? Unlike what we many think, the sonic identity of a brand is not its jingle or its sonic logo. Just as a visual brand identity is not a mere logo, but a set of colors, images, graphic elements and symbols, sonic identity is also a much broader set of sonic assets.

The application of these sonic assets to the customer experience is a brand’s sonic identity.

To create a quality sound identity, it is therefore essential to apply the same strategic rigor and creative thinking that underlie visual identities. Starting from the definition of sound and vocal principles, then by identifying a brand’s instruments, melodies and chords, it will be possible to compose your own sound asset, which can include: sonic logo, interaction sounds, branded soundtracks, playlists, and podcasts. Obviously, the greater the sonic assets, the more touchpoints can be covered within the experience offered. From products to experiences, from events to online platforms and social media, from shops to payment times, brands can create strong relationships with their consumers through sound identities.

For this reason, there are already many brands that, from banking to automotive, from fashion to food & beverage, are experimenting with sound identities, highlighting the importance of an aural dimension within a successful brand strategy. Emotionally involved sound has no linguistic or cultural barriers and allows you to reach everyone in a meaningful way.

Do you want to find out more about the future of sound and its applications? Write to info@old-maize.lndo.site, and our strategic think tank will be able to provide you with a unique perspective on the topic.